A tale of memory layots and a MCU

Last updated: Aug 26, 2023

The code shown in this post is available at ronyb29/pyAN575 and in PyPI as pyAN575

Some time ago, trying to communicate with a Microchip MCU I noticed all of the float values were wrong. The rest of the fields were fine, just the float values were getting scrambled. After looking around a bit I ended up talking to Chris, who I recalled having a similar problem in the past, he told me the float format for some of Microchip’s products is different that the standard moderns computers use. Well, that sucks, but maybe we can do something.

Many MCUs don’t have hardware support for floating point operations, including the microchip PIC16/17 families. Instead, float support is implemented in software. At some point Microchip released an application note (AN575), so some people just call the format AN575, here they use a different memory layout in favor of performance, which sounds a little crazy, but remember we’re talking MHz here and some of the operations might still take almost a thousand cycles, so every tick counts.

Because of the inherent byte structure of the PIC16/17 families of MCUs, more efficient code was possible by adopting the above formats rather than strictly adhering to the IEEE standard.

– Testa, Frank J., “IEEE 754 Compliant Floating Point Routines”, Microchip, 1997

To understand what we can do let’s explore what the differences are, after all the application note implies that the difference is just a small optimization.

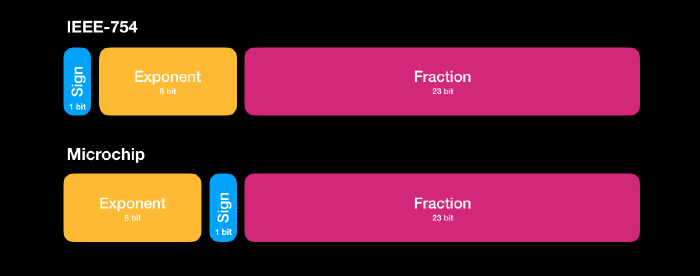

Both formats store floats as 32 bit values with 3 homologous fields: sign, exponent and fraction (or mantissa). They are ordered differently in memory though, we can see the layouts in Figure 1. There’s also a spec for a 24 bit float with a 15 bit fraction, I will gloss over it because if 32 bit floats are already weird, 24 bit floats … well, let’s not talk about those.

It seems simple enough to de-scramble the pieces and convert them back and forth. Let’s take a look at how I did it in Python.

I think what we need here is a special kind of struct called a bit field, this is basically a struct that has different bit lengths specified for its values. If you’ve read some C code before, specially if it was intended to interact with hardware, you might have seen something like this:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdint.h>

typedef struct {

uint32_t partA:23;

uint32_t partB:8;

uint32_t partC:1;

} ThreeParts;

int main(void) {

ThreeParts value = {65539, 255, 1};

printf("%lu\n", sizeof(value));

return 0;

}

It says that the 3 fields in ThreeParts share the space in different proportions, 23 bits for partA, 8 for partB and 1 for partC. There are a few rules that determine the actual size of the struct in memory, including the type and order in which the bit fields are declared and wether the struct is packed or not. In the case of the floats, we only need 32 bits which matches uint32_t, in fact ThreeParts already encodes the IEEE754 layout for a regular x86_64 pc. There are some nuances for actually doing the conversion, but it’s easier to deal with those in python.

Python usually comes with a module called ctypes (depending on compilation options). It’s intended for loading native binaries in runtime and calling functions on them (FFI), it also has some utilities to make memory layouts easier to deal with from python, which is necessary when a native function receives a struct for example.

In our case we aren’t calling any native functions, but we’re using ctype’s utilities for dealing with bit fields, thankfully those deal with the nuances of endianness, the order in which bytes are stored in memory, which is sometimes troublesome. In our case we’re using network endianness to represent our struct, since we’re doing proper conversions (as opposed to copying memory blindly) this shouldn’t be an issue. Let’s see some code.

from ctypes import c_uint32, BigEndianStructure

from struct import pack, unpack_from

class Ieee754Float(BigEndianStructure):

"""

Regular float that we're used to in modern computers

"""

_pack_ = 1

_fields_ = [('sign', c_uint32, 1),

('exponent', c_uint32, 8),

('value', c_uint32, 23)]

def __float__(self):

return unpack_from('!f', self)[0]

@staticmethod

def from_float(f: float):

buff = pack('!f', f)

return Ieee754Float.from_buffer_copy(buff)

Here we are using a BigEndianStructure. It let us define a set of _fields_ each with an optional length, in this case 1, 8 and 23. We could have used LittleEndianStructure, but in a well behaved communications channel the data passing through should be “network endianness” which is always big endian.

We’re also implementing a magic method to be able to cast our Ieee754Float as a float just using the built in float(). We’re using pack and unpack_from to convert from native floats to a bytes object and vice-versa, the first argument to both is a struct format string ('!f') in this case were saying we’re working with a big endian (!) float (f) because we’re using a BigEndianStructure.

Finally from_buffer_copy comes for free because we inherited BigEndianStructure. It just copies the underlying memory from a bytes object to out struct.

That takes care of representing the IEEE-754 floats. Now let’s look at the Microchip AN575 representation.

class An575Float(BigEndianStructure):

"""

Microchip 32-bit float format as described in

Application Note AN575.

"""

_pack_ = 1

_fields_ = [('exponent', c_uint32, 8),

('sign', c_uint32, 1),

('value', c_uint32, 23)]

def __float__(self):

result = Ieee754Float()

result.exponent = self.exponent

result.value = self.value

result.sign = self.sign

return float(result)

@staticmethod

def from_float(f: float):

ieee = Ieee754Float.from_float(f)

an = An575Float()

an.exponent = ieee.exponent

an.value = ieee.value

an.sign = ieee.sign

return an

Here we’re just moving the fields from an object to the other. Since we could leverage ctypes we don’t have to get our hands too dirty by dealing with bit shifts and instead use a declarative syntax.

I wish BigEndianStructure and its sisters LittleEndianStructure and Structure had better type hint support, perhaps by using a special dataclass, maybe that’s worth an in-depth look in the future.

ctypes is extremely useful for talking to MCUs and dealing with hand-made data frames. If you have to deal with this kind of thing in your day to day give it a try.